Breadcrumb

- Home

- Outdoor News Bulletin

- June 2025

- Public Lands: Acres, Dollars, and Identities

Outdoor News Bulletin

Public Lands: Acres, Dollars, and Identities

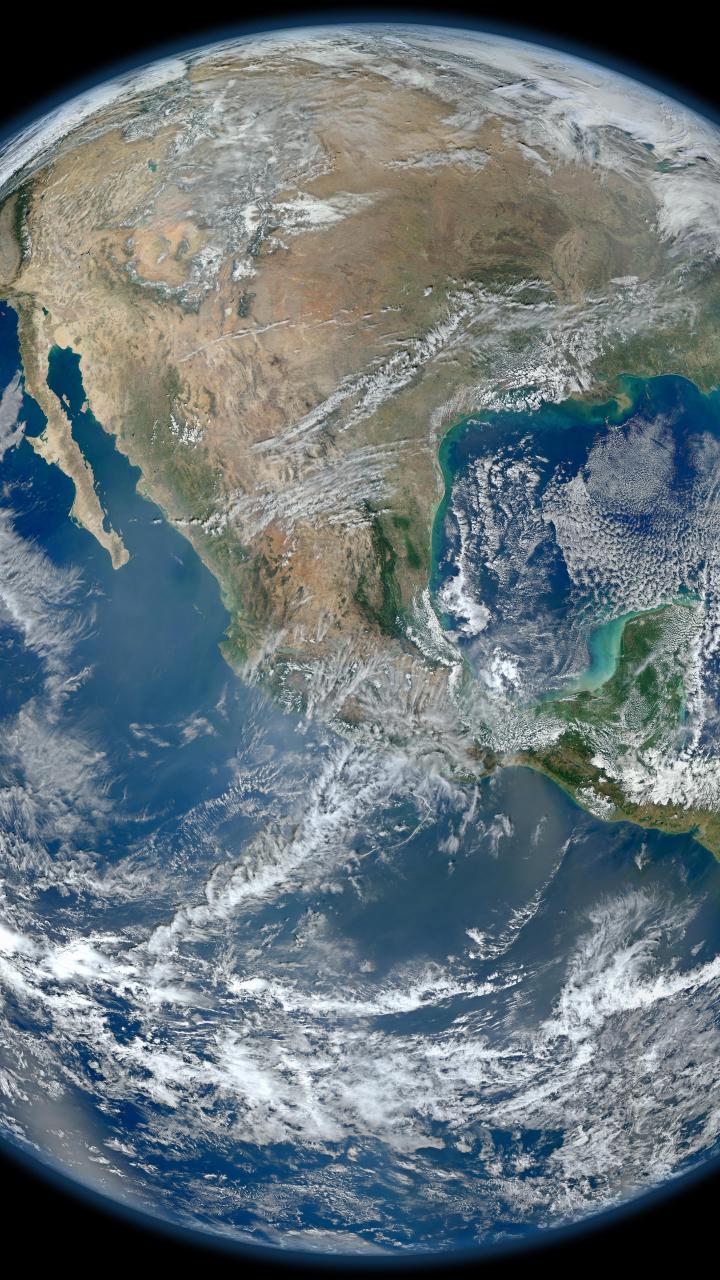

Since the creation of the current model of western conservation, there has existed a struggle for broader societal relevance. The expression “societal relevance” is really just a way of expressing society’s level of awareness and regard for an issue. Most people in the conservation arena aspire for conservation as a practice to be more widely valued with more people caring about the effective conservation of wild animals, wild places, or some combination thereof, often including other natural resources like soil and water.

Evidence of the struggles for conservation relevance includes historic examples of unlikely alliances like that of garden clubs and hunters. Instances in which two parties share a common goal, yet neither party is sufficiently relevant, creates novel and unlikely partnerships.

In the early 20th century, garden clubs and hunters—seemingly disparate groups—joined forces to advance conservation efforts. Conservation was equally important to the two groups albeit for different reasons, and neither garden clubs nor sportsmen in and of themselves held sufficient societal relevance to achieve their desired conservation-related outcomes. Through the joining of forces to collectively advocate and amplify coproduced messages, the Garden Club of America along with hunters helped to play a key role in shaping the conservation movement.

There are also modern examples of efforts to achieve greater relevance for conservation like the Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ (AFWA) and Wildlife Management Institute’s (WMI) Relevancy Road Map. History is replete with examples of efforts to elevate the importance of conservation in society. The ultimate questions at hand include, “What makes people aspire to conserve something?” and “How can you motivate people to want to protect something?”

The Importance of Connection

Several ideas and concepts pertaining to how individuals develop a sense of stewardship have been explored and expressed through the years. One set of ideas explaining the development of a conservation ethic that I find particularly resonant is built on a foundation of connection—connection to a place or connection to a species. Writers like Wallace Stegner and Barry Lopez and poets like Gary Snyder all strongly emphasize the importance of place and connection, viewing them as intertwined with human identity and our relationship with the natural world. In various ways, each writer advocates for a sense of belonging to a particular place, understanding its ecological systems and history, and seeing humanity as an integral part of those places. This connection fosters an interest and intrigue about the places or species. As one spends more time, studies, and learns more, respect for both the species and the systems typically results.

Respect for the uniqueness, splendor, natural history, or other perceived redeeming aspects develops and grows, ultimately motivating. An entire army of non-governmental organizations (NGOs) and conservation volunteers has been built by this seemingly simple progression. Through connection, respect is developed and ultimately inspires one to protect. Simple: connect, respect, and protect.

Sheep, deer, elk, pronghorn, ducks, pheasants, turkeys, trout, bass, and so many others, including place-based organizations, are populated with deeply passionate members whose catalyzing interest in a place or species was born from connection and many times the result of a recreational opportunity. So many of the historically, ecologically, geographically, and culturally significant areas have place-based efforts focused on protection. The significance of place is particularly evident in indigenous cultures. Not only have indigenous cultures relied on sacred places for their culture’s survival for thousands of years, but they also have witnessed life and death of their people in these places, and paid tribute to and buried those lost there as well.

The Growing Disconnect

If the desire to conserve natural resources is ultimately derived from a personal connection to them, there are some concerning trends with respect to species and systems connections in today’s society. Today’s society is increasingly mobile. We spend less time in any one place and scatter ourselves in often less meaningful ways and in many more and often disparate locations. This pattern of presence, or lack thereof, ultimately hinders the ability to develop a meaningful connection to place. Often, when in those disparate places, the constant digital distraction of phones, social media, and ever-present Wi-Fi, further hinders our ability to be fully present in forming deep and reflective connection.

Conservation is not a unique victim of the growing disconnect. Food procurement and the farming industry, wood products, minerals, water, and energy have all grown disconnected from the end user. People seldom know of the source or impacts of the energy generation meeting their daily energy demands. Wood products for homes, water from the tap, and minerals for industries are often taken for granted without an awareness of the costs and impacts resulting from their procurement. Aldo Leopold recognized the threat of this disconnect and wrote succinctly of it in his A Sand County Almanac when he said, “There are two spiritual dangers in not owning a farm. One is the danger of supposing that breakfast comes from the grocery, and the other that heat comes from the furnace.”

In our ever distracted and disconnected society in which we are bombarded with constant messages, imagery, and ever-present digital connections, our connection to the natural world often suffers. I fear we, as a society, are conditioned to grow bored without constant bombardment, we are conditioned to be ever intrigued by the novel and in so, we often fail to achieve the types of deep purposeful connections that Stegner, Lopez, and Snyder, among others, wrote about.

These writers all strongly emphasized the profound connection between humans and place, arguing that understanding and appreciating our surroundings is essential for both individual well-being and the health of the planet. They believed that immersing ourselves in a specific location, whether through prolonged residency or deep exploration, leads to a reciprocal relationship where we not only learn about the place but also, in turn, become known by it. This connection, they all suggested, can foster a sense of belonging and develop a strong sense of stewardship. A sense of stewardship that is not only essential for effective conservation but also a sense of stewardship that without connection, is rare and unlikely to exist.

Public Lands – More than Acres and Dollars

Perhaps one of the best examples of connections is through our public lands. As public land sales have been increasingly in the spotlight, it has me thinking about the various perspectives and emotions that selling public lands evokes. I reside in the 7th largest state, Nevada, that has an often cited 85% federally administered land. This is the single largest percentage of federally administered land in any state and is second only to Alaska in total acres of public land. From that perspective, I understand that we don’t need every single acre of public land that currently exists. There are acres of federally administered land in Nevada that presently offer little in terms of habitat for species, recreational opportunity, or little else immediately evident through a solely human lens. Despite that, the very idea of public land sales is at face value a non-starter for many. Why is that? Aside from the justifiable process-related concerns, I suppose the notion is found strongly objectionable by so many because of what it represents in terms of principal and precedence, and perhaps connections to the land.

If it is through a connection to public land as a place that an individual’s identity is found, selling these precious places can undermine and erode the very identity of an individual. Again, I’m reminded of how the stripping of land from indigenous cultures was robbing them of their independence and identity. Additionally, even if the lands being proposed for sale are not the very same places to which those objecting to the sales are connected, the precedent of allowing the sale of some public lands invites contemplation of what may be sold next.

Conservation resides at a critical crossroads struggling to increase its relevance, continuing the pursuit of dedicated funding for whole wildlife conservation, and trying to recruit more people into the fold whether as hunters, anglers, birdwatchers, or simple nature enthusiasts.

As people’s deep connections and personal identities are formed and found on these lands, their sales can erode an individual’s sense of being. Clearly, the depth of emotion, the varying opinions on how and where lands should be maintained or sold, and the distance to those connections all matter in how people are approaching this issue. One thing that is clear, people want their voice to be heard. Individuals less connected to these lands understandably find the notion of land sales less objectionable as the loss of the land has little to no impact on those lacking connection to the land or lacking any connection to the species residing there and depending upon it.

Perhaps this is one of the many reasons that Aldo Leopold’s committee, upon writing the 1930 American Game Policy, presented their first of seven fundamental actions necessary for effective conservation, specifically pertaining to public land ownership. Written nearly 100 years ago in 1928 and published in 1930, Leopold’s committee asserted that an effective conservation program must begin with seven basic moves or actions. Number one of those seven actions was to “Extend public ownership and management of game lands just as far and as fast as land prices and available funds permit. Such extensions must often be for forestry, watershed, and recreation, as well as for game programs.”

Conservation resides at a critical crossroads struggling to increase its relevance, continuing the pursuit of dedicated funding for whole wildlife conservation, and trying to recruit more people into the fold whether as hunters, anglers, birdwatchers, or simple nature enthusiasts. Our ability to grow interest and relevance for conservation is dependent on access to recreational opportunity to foster connection. A loss of public lands potentially hinders our ability to curate nature experiences. Nature-based experiences are critical in fostering a stewardship-minded citizenry that is so important to the future of conservation, our quality of life, and ultimately our health and well-being.

Do we need all our public land? Maybe not, but we darn sure need more opportunities to connect people with nature as humanity’s ability to effectively protect nature is a consequence of our ability to connect to it. The loss of special public land places is critically important to conservation because place is not just a location but a powerful force that shapes our understanding of ourselves, our history, and our place in the world. I believe in the importance of preserving wild places and wild species, both for their intrinsic value and for the sense of connection and belonging they offer humans and ultimately, what they give back to humanity.